The westernwear starts appearing a few stops away from the Forest Avenue stop in Ridgewood: When I look up from my phone, I notice someone in bright-green cactus-print pants, a patchwork leather coat, and a bandanna. “I’m accepting that I’m now firmly in my yeehaw era,” Marlee Newman tells me as we both get off the train and head for Gottscheer Hall.

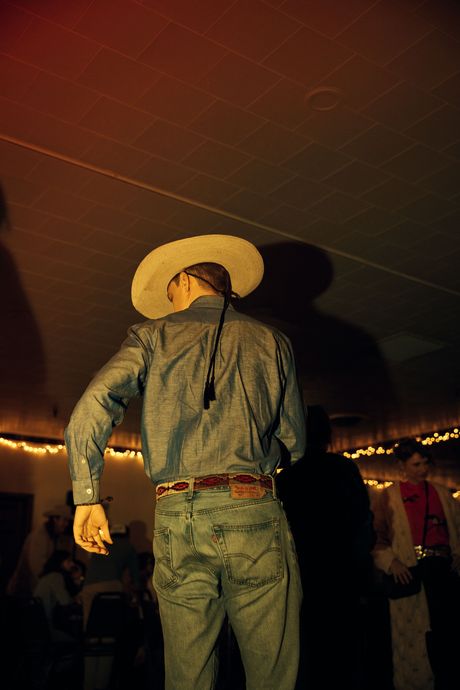

The back room of the 100-year-old bar and social club, with its drop ceilings, carpeted floors, and bartenders serving drinks behind a row of folding tables, feels comfortably shabby, designed to dust off any sense of pretense from the people who enter. The crowd includes Gen-Zers in prairie dresses and Big Bud Press jackets and old-timers who have been dancing for decades in whatever New York bar allowed a fiddle at the time. Everyone’s here for Honky Tonkin’ in Queens, one of the biggest regular country-dancing events in the city. “This is exactly like Nashville,” I hear someone say.

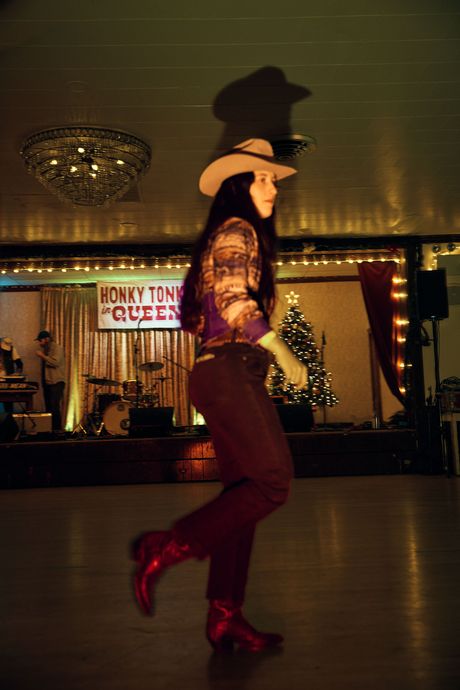

Not that long ago, people in New York City bars “would hear country and walk right back out,” says Charles Watlington, who started the event a year ago with fellow DJ Jonny Nichols. It wasn’t until the self-described honky-tonk Skinny Dennis opened in Williamsburg in 2013 that the pair, who go by DJ Moonshine and DJ Prison Rodeo, found a spot that was dedicated to their chosen genre beyond the occasional country night. Of course, New York has always had a handful of places like this; I talk to an older man who met his wife on the dance floor at a Staten Island bar called Pony Express back in 1997. A pack of friends dominating one corner met at a line-dancing night held every Wednesday at the Ukrainian National Home in the East Village, and several people mention Jalopy in Red Hook, a theater and music school focused on traditional roots music. But Watlington and Nichols are convinced that it has all reached a boiling point — and Honky Tonkin’ in Queens is selling out every time. “I feel like people just wanted something like this,” Watlington says. “I had somebody tell me at the second show, ‘This is like the Studio 54 of now.’”

By the time the first act, Brooklyn-based North of Amarillo, goes on, the dance floor is half two-steppers, half line dancers — with a strip of painter’s tape separating the two, though not without occasional territory disputes. I find Cammi Climaco and Cru Jones playing poker at a table near the back wall; they live nearby and have been to the past six shows. “The line dancers — it’s like a shark: You don’t want to get in their way. They just keep on going,” Jones tells me. He’s in a heavy-metal band, but he’s also been into country music since his childhood in Ohio. “I think a lot of older heavy-metal guys are starting to play Americana,” he says. “Maybe it’s the honesty of the music. It’s also a good way to slow down, not yell or jump around as much.”

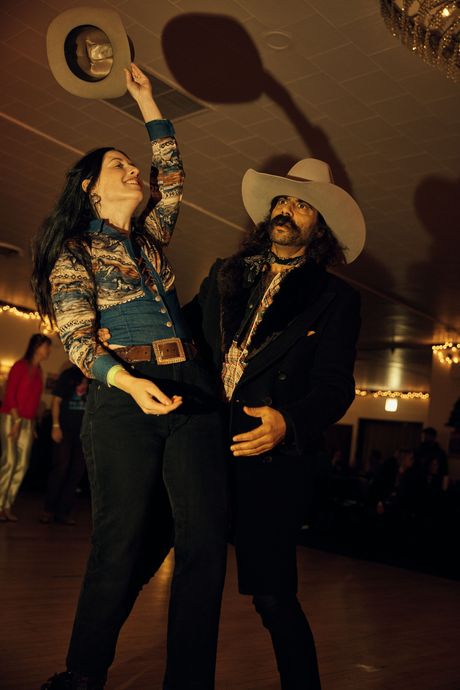

Nearby, a cluster of friends in their 20s and 30s is celebrating a birthday in fringe, denim, and sheer red looks (“This shirt is actually a vulva,” one of them tells me, pointing to her wavy collar and pearl button). Another group, with tattoo sleeves and dyed-black bangs, is made up of refugees from a rockabilly night that fizzled out last fall after about 18 years. Their preferred style of dance, rockabilly jive (“It’s like drunk swing,” Eddie Chow says), works well enough here in the two-stepping area. The two founders of L.A.-based Stud Country, a queer country-dancing class, Sean Monaghan and Bailey Salisbury, observe the scene from a table with their dog, Bianca. “I think people are realizing that line dancing is fun and sexy and hot,” Salisbury says.

By the bar, I talk to an actual Gottscheer — Joe Kikel, whose parents immigrated to Ridgewood from the Gottschee region in Slovenia. Now, his son bartends here. Kikel seems happily amused by the scene in his hometown bar. “I’ve loved country music my whole life,” he says, and the mood is unusually chummy. When I elbow through the crowd and tap one guy on the shoulder to see if I can interview him, he immediately asks if I want to dance. Later, he introduces me to all his friends. “I’ve seen 77-year-olds dancing with 20-year-olds,” Watlington says.

The second act is Laura Cantrell, who’s been a fixture in the city’s country scene since moving here from Nashville in the ’90s. “I just assumed, coming to New York, that there wasn’t going to be any country music, but there were these rich pockets of it,” she says. She thinks the current enthusiasm for it is new, however: “It’s another instance of New York’s country culture bubbling up and surprising me.” Cantrell is followed by Lola Kirke, a younger artist (and actress Jemima Kirke’s sister, as several people I interview remind me; that’s probably the second-most-popular talking point, after Beyoncé’s new country song) whose musical output has become increasingly twangy since she started putting out albums in 2018. She appears with an acoustic guitar and a five-piece band, wearing a pink cowboy hat and a Dolly-esque baby blue minidress. As Kirke banters through her set, the room gets looser — the vibe is drunk and flirtatious, and the dancing is becoming more, well, social. I see a couple making out in a corner near a middle-aged woman twirling around in a long-sleeve sequin top. Once Kirke launches into a cover of “Hit Me Baby One More Time,” the finer rules of two-stepping are forgotten — aside from a few holdouts, everyone lets go of their dance partner and faces the stage to shout along.